On April 14 Boko Haram, a Nigerian Islamic terrorist group, kidnapped over 200 girls from their school in the rural town of Chibok located in Borno State in Northern Nigeria. They reportedly planned to convert each of the girls into Muslims and sell them off as brides. Boko Haram later released video footage of some of the girls reciting Muslim prayers.

The incident sparked an outcry on social media, which resulted in the popular hashtag, #BringBackOurGirls. Protestors across the globe also took to the streets.

The organizers for one demonstration held last month in New York City asked female attendees to “rock a crown” (a head wrap), to show solidarity with the mothers of the young women who were violently stolen.

When I first saw the invitation to the rally, my emotions kicked into full gear for the young women of Chibok. I thought about how on-trend head wraps have become. A part of me wanted all of us to put our good fashion sense on pause. Did the mothers of these young women really need us to wear a gele or a turban to show solidarity? Clearly our headgear would be the furthest thing from their minds at such a trying time.

I went to the protest and snapped the photo above, among others. To date, I think it’s one of the best images I’ve taken since I began conceptualizing my idea for ScriptsandSightings.com. The ladies in the photo exude a sense of dignity, which I believe is a protest in and of itself. Their head wraps simply added to that power.

Then I remembered how other articles of clothing have been an important symbol for various protests and revolutions—particularly involving Africans and African Americans—throughout the years. Here are a few examples:

Huntsville Alabama—Blue Jeans Sunday

In the 1960s, African American residents in Huntsville, Alabama were not allowed to use restrooms at department stores or even try on clothes and shoes. Members of the city grew tired of the prejudice and decided to take action.

On Easter Sunday, April 21, 1962 African Americans were encouraged to wear blue jeans and denim skirts to church instead of fancy Easter clothing. The little known boycott— which was dubbed Blue Jeans Sunday—was designed to hit the merchants where it hurt: their profits. Easter was a time when stores in the area sold the most suits and dresses. After the boycott, it was estimated that those businesses lost nearly one million dollars that Easter weekend. Three months later Huntsville merchants decided to end segregation in their establishments, making it the first integrated city in Alabama.

Keep in mind, wearing denim in the 1960s wasn’t the fashion statement that it is today. So I imagine, going to church on Easter Sunday in jeans was a real sacrifice for the people of Huntsville. It eventually paid off.

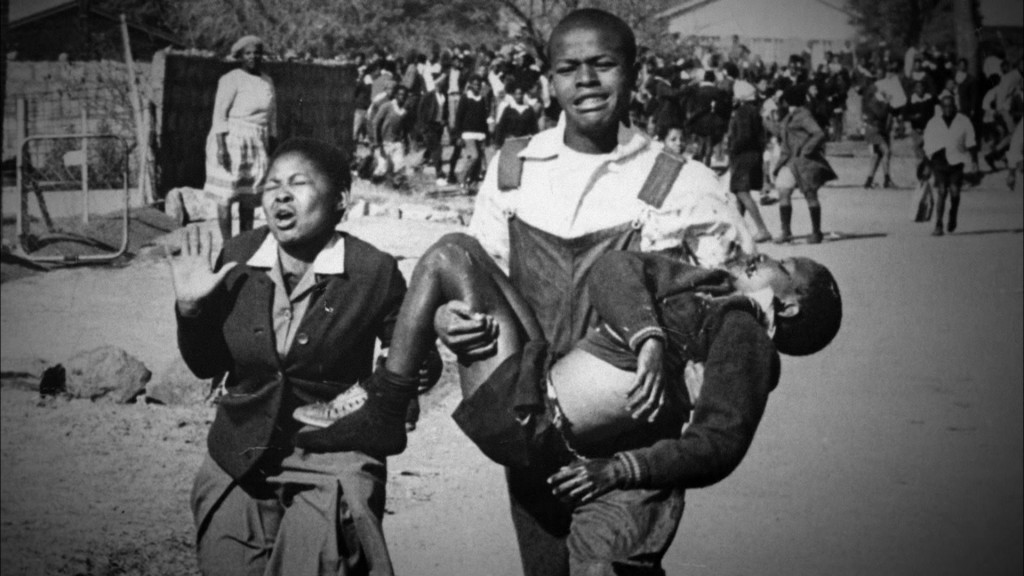

Soweto Uprising—School Uniforms

When I think of South Africa’s battle against apartheid and the various uprisings that took place, I first picture school children wearing school uniforms engaged in protest. Beginning June 16, 1976 Soweto students began protesting the Afrikaans Medium Decree, which declared Afrikaans the new official language for instruction in schools.

What started out as a peaceful demonstration on a school day turned into a bloody stampede after police opened fire. It’s estimated that up to 700 students were killed, including Hector Pieterson whose bloody body was photographed being carried away.

Unlike other protests the students of Soweto didn’t choose to wear anything in particular, they were simply going to demonstrate on a school day. Their knee length skirts, pinafores, slacks, V-neck cardigans, and stiff collared shirts helped to create an important picture. Their uniforms were a symbol of youth. As we are able to look at photos from that historic moment, the clothes on their backs are a reminder that teenagers were literally attacked by the bullets of policemen. We’re also reminded that it was the youth of South Africa who dared to stand up against the government years after their parents’ generation had been silenced. It was the beginning of a revolution.

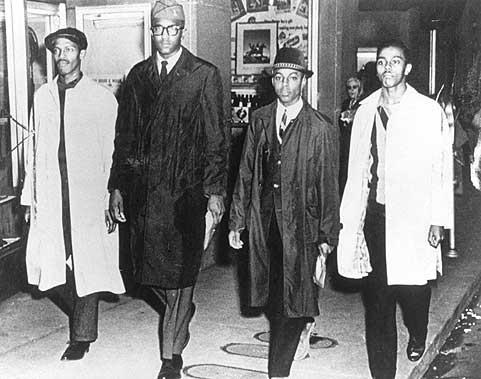

Civil Rights Sit-ins—Professional Attire

On February 1, 1960, four African-American students dressed in blazers, slacks, ties, and trench coats sat at the segregated “whites-only” lunch counter at F.W. Woolworth drugstore in Greensboro, N.C. The students—Ezill Blair Jr., David Richmond, Joseph McNeil, and Franklin McCain—asked to be served. They were told to leave. The men remained seated at the counter until the store closed at 5:30pm.

Their brave act inspired many. The four men went back to Woolworth the next day with other students who were willing to join the cause. The participants were encouraged to act in a non-violent manner and dress professionally. By October Woolworth and several other chains desegregated their lunch counters.

Their professional attire sent a clear message: I am dignified, I am someone, I am human. Though a suit shouldn’t determine a person’s level of humanity, in many cases, people of color have to work the hardest and look their best to assimilate into American society.

Black Panthers—All Black Everything

Black berets, black shot guns, and black leather jackets made up the uniform for members of the Black Panther Party. Their gear spoke volumes. The guns represented their main stance: self-defense against racial crimes and injustice. The beret, often worn by army officers across the globe, served as a symbol of militancy.

J. Edgar Hoover, who was the director of the FBI at the time, had been so shaken by the Panthers’ images and overall mission, he called them “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country.” Then he launched a secret campaign to undermine the group.

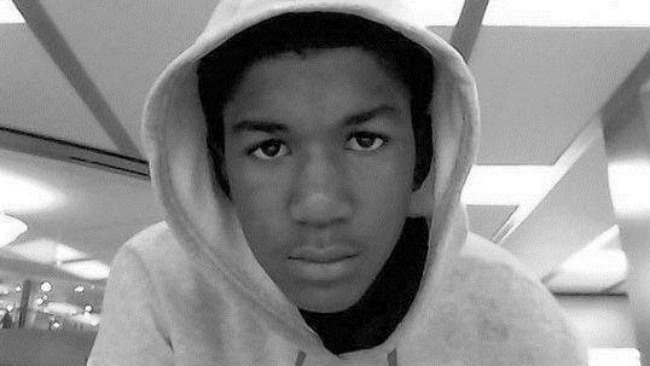

Trayvon Martin—The Hoodie

After the killing of Trayvon Martin became big news and sparked various protests in 2012, the hoodie transcended from street wear status into something weightier. At times it felt as though Trayvon’s killing was getting lost in the abyss of filtered Instagram pictures of people wearing a hoodie in solidarity with Trayvon’s family. But it was that massive outcry on social media that brought awareness to Martin’s case, which in turn led to the arrest of George Zimmerman, the man who shot him.

The significance of the hoodie became even more apparent this year after Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban decided to use it as an example of his own prejudice against individuals dressed a certain way. A slew of people on social media shamed him for referencing the hoodie, calling his comments insensitive. He later apologized to Trayvon’s family.

It was clear then that the hoodie, for many people, had become almost as sacred as—dare I say—the cross is in reference to Christ. Both are a symbol of the persecution and death of the innocent.

It’s safe to say that the hoodie has reached a status that many articles of clothing simply cannot and likely will not.

Can you think of any other examples on how clothing has shaped protests and revolutions worldwide? Share your thoughts below.

Side note: Going back to the story of the Chibok girls of Nigeria, it saddens me that they still haven’t been rescued. What’s even more disturbing is the fact that Boko Haram has killed more people in Nigeria since the incident. The Nigerian government hasn’t done much to address the issue and the social media campaign, #BringBackOurGirls has pretty much fizzled out. The media and the average person on Twitter have moved on to the next “sexy” hashtag making headlines. Did we “rock our crowns” in vain? The struggle continues.

[…] Read the whole story at scriptsandsightings.com […]

[…] Read the whole story at scriptsandsightings.com […]

Great work my friend! I enjoyed reading and viewing everything! Very moving!

Orginal story great work!!!

Keep it coming!!!

Great article! I loved the theorized historical events and your point of view about it all; to include how fashion played a role. This piece makes a huge statement and your hard work will continue to pay off. Keep writing and inspiring. Love love it!

[…] Read more at ScrapsandSightings.com […]

[…] revolutions—particularly involving Africans and African Americans—throughout the years.” Scripts and Sightings explores where fashion history and social justice meet and […]