“Not all African women believe black is beautiful. And that’s ok.”

When I first read that headline for an opinion piece written by Nigerian journalist, Sede Alonge for the UK Telegraph, I was ready to take to my laptop to write a heated retort.

Alonge wrote her piece in response to the backlash Kenyan model and socialite Vera Sidika received after she revealed her new look. The once brown beauty admitted that she underwent rigorous procedures to bleach her skin to a near ghost-like fair complexion. In Alonge’s op-ed regarding the matter, she argues that it’s okay for some black women to feel their blackness isn’t beautiful and that white people are also guilty for skin transformations such as tanning.

According to Alonge:

Yes, black is beautiful, but so also is white, brown, yellow and the many shades in between.

When white people use tanning lotions, solariums and other methods to darken their skin, it is treated as par for the course and other white people don’t feel the need to remind them that “white is beautiful”. In fact, such a statement would likely be regarded as racist by members of other races. Yes, I understand that there was a specific historical context in the US and elsewhere which, at the time, necessitated the use of the “black is beautiful” slogan in order to boost black people’s sense of self-worth and identity, but this is 2014 and we should have gotten beyond that by now. Or are self-affirming slogans going to be needed by black people forever?

People’s desire to have a particular skin tone, be it a darker or lighter one, stems from them wanting to be more attractive and sometimes for others to take notice. And more often than not, in the case of an individual who has undergone skin lightening here in Africa, it works. The critics might be unwilling to concede this publicly, but the harsh truth is that in Africa, lighter skinned girls do get more attention and are more appreciated than darker skinned women.

After reading Alonge’s words, I wanted to inform her that skin tanning simply doesn’t hold the same weight as colorism—a deep issue within the black community laden with racial baggage. I believe it’s the very reason bleaching agents are being sold like hot cakes among black women, especially in Africa. In Nigeria alone, 77% of women reportedly use skin lightening products according to the World Health Organization. Furthermore, even in 2014 white women are considered the standard of beauty in the western world regardless of how pale or tan they are. Therefore “self-affirming slogans” like “black is beautiful” will endure.

I also wanted to address Vera Sidika’s transformation. But as I constructed the story in my head, I realized that many of the things I wanted to say have been said time and again: That black is indeed beautiful; That we should love ourselves; That colonialism and slavery are at the root of why we’ve been conditioned to believe we are not beautiful; That a rejection of your God-given black skin is an obvious form of self-hatred; That a rejection of your dark skin is a rejection of me and women who look like me; That when women change their complexions they are indirectly telling young girls who are dark skinned that they aren’t good enough. We’ve heard it all before. We’ve read such articles; we’ve watched the documentaries.

Plainly stated, when an adult seeks to attain to a certain aesthetic, there’s likely no changing that person’s mind, and they have that right. In that regard, I agree with Alonge. So why, I asked myself, should I waste my time writing a preachy response regarding a personal decision? Maybe, instead, what I should feel is compassion for a person who changed their appearance in such a way. Afterall, it’s not easy for women to navigate in a society that puts so much weight on beauty.

The over emphasis on outer appearance makes me recall an interview Britain based Nigerian author Helen Oyeyemi did with NPR some time ago. The young novelist who’s been deemed a literary prodigy admitted that she considers herself ugly but interesting. My initial reaction was shock, but eventually I realized how important and liberating her declaration must have been. She was able to detach herself from the thing that holds many women hostage and get on with the business of being intelligent and dynamic. That courage was likely the motivation she used to write her first novel before she graduated from high school. By the time she was 19, she signed a two-book deal reportedly worth $1 million. Not many grown women boast that level of accomplishment in their chosen field.

As a mother of a young black girl, I know my purpose is to show her that she is indeed good enough—not simply because of her looks or her complexion, but because she is a divine being worthy of all that is good. I will do my job in this regard.

So rather than write preachy responses, I will work to showcase all that makes little black girls and black women beautiful regardless of their appearance. It’s one of the reasons I chose to focus on people of color for this blog. I wanted to document the fact that we are here and we deserve to be celebrated, because many of us are proud of who we are and we express that pride through all forms of unique style.

So I will no longer seek to berate a grown woman about how she feels about her blackness. There are books available if people want to know their history. There are magazines and websites that celebrate who we are. There are organizations that seek to spread the overall message. If by now responsible adults don’t know black is beautiful, there’s not much else to say to change their minds. For those of us who are aware of our greatness, let’s focus on celebrating ourselves in the presence of young black people. Instead of simply telling black youth they are beautiful, let’s begin to show them exactly why they should love who they are, aesthetic and all.

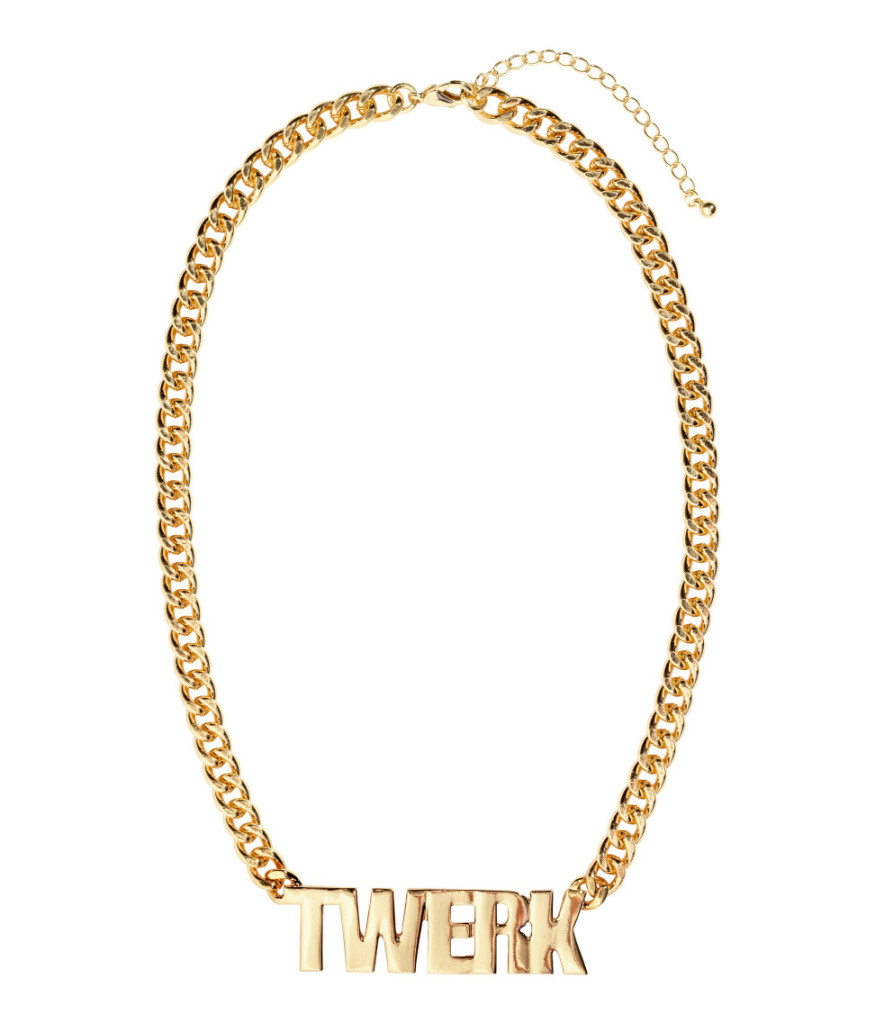

Within the span of 15 years twerking went from an average hip-hop dance to the internet’s worst kept secret. Twerking was reportedly introduced to United States in the early 90s by DJ Jubilee, who created the first recorded song using the word “twerk.” Since then it’s been popularized by the likes of New Orleans’ “Queen of Bounce,” Ms. Freedia. In the early 2000s artists like the Ying Yang Twins, Beyonce, and Ciara referenced it in their music and performances. But twerking remained a mere dance on the list of many within hip-hop culture. Things started to shift after Youtube became a playpen for camera thirsty Twerk enthusiasts.

Whether you warmed up to the provocative dance or not, there’s no question that it sparked a phenomenon in culture and fashion. Who could scroll through their Instagram feed without seeing someone wearing a T-Shirt referencing their support for twerking? Almost everyone was a twerk team captain.

On April 14 Boko Haram, a Nigerian Islamic terrorist group, kidnapped over 200 girls from their school in the rural town of Chibok located in Borno State in Northern Nigeria. They reportedly planned to convert each of the girls into Muslims and sell them off as brides. Boko Haram later released video footage of some of the girls reciting Muslim prayers.

The incident sparked an outcry on social media, which resulted in the popular hashtag, #BringBackOurGirls. Protestors across the globe also took to the streets.

The organizers for one demonstration held last month in New York City asked female attendees to “rock a crown” (a head wrap), to show solidarity with the mothers of the young women who were violently stolen.

When I first saw the invitation to the rally, my emotions kicked into full gear for the young women of Chibok. I thought about how on-trend head wraps have become. A part of me wanted all of us to put our good fashion sense on pause. Did the mothers of these young women really need us to wear a gele or a turban to show solidarity? Clearly our headgear would be the furthest thing from their minds at such a trying time.

I went to the protest and snapped the photo above, among others. To date, I think it’s one of the best images I’ve taken since I began conceptualizing my idea for ScriptsandSightings.com. The ladies in the photo exude a sense of dignity, which I believe is a protest in and of itself. Their head wraps simply added to that power.

Then I remembered how other articles of clothing have been an important symbol for various protests and revolutions—particularly involving Africans and African Americans—throughout the years. Here are a few examples:

Huntsville Alabama—Blue Jeans Sunday

In the 1960s, African American residents in Huntsville, Alabama were not allowed to use restrooms at department stores or even try on clothes and shoes. Members of the city grew tired of the prejudice and decided to take action.

On Easter Sunday, April 21, 1962 African Americans were encouraged to wear blue jeans and denim skirts to church instead of fancy Easter clothing. The little known boycott— which was dubbed Blue Jeans Sunday—was designed to hit the merchants where it hurt: their profits. Easter was a time when stores in the area sold the most suits and dresses. After the boycott, it was estimated that those businesses lost nearly one million dollars that Easter weekend. Three months later Huntsville merchants decided to end segregation in their establishments, making it the first integrated city in Alabama.

Keep in mind, wearing denim in the 1960s wasn’t the fashion statement that it is today. So I imagine, going to church on Easter Sunday in jeans was a real sacrifice for the people of Huntsville. It eventually paid off.